Canadian Thanksgiving is an annual cultural holiday observed on the second Monday of October. It has been officially recognized since 1879, and since 1957 it has been fixed to its current date. While today it is a time of gratitude, family gatherings, and seasonal feasts, the history of Thanksgiving in Canada is both fascinating and complicated.

Early Roots and Historical Moments

The story of Canadian Thanksgiving is not tied to a single event, but rather a series of occasions where European settlers expressed thanks. One of the earliest examples dates back to 1578, when explorer Martin Frobisher and his crew held a feast of thanksgiving and prayer in Newfoundland after surviving a dangerous journey through the Arctic in search of the Northwest Passage. Later, in 1606, Samuel de Champlain organized a Thanksgiving celebration in Port Royal, Nova Scotia, through the “Order of Good Cheer,” which included local Mi’kmaq people.

Over the years, similar gatherings took place, often in autumn and usually linked to harvest time or survival after difficult journeys. Many of these occasions reflected Protestant traditions of thanking God for blessings. After World War I, Thanksgiving in Canada was temporarily tied to Armistice Day, before Remembrance Day was established separately and Thanksgiving was set permanently in October.

A Complex Relationship with Nation-Building

As highlighted in a Macleans article, Canadian Thanksgiving also carries a complex legacy. Like its American counterpart, it has often been presented as a moment of unity between settlers and Indigenous peoples. In reality, both European and Indigenous societies already had harvest feasts and thanksgiving traditions long before their interactions.

More critically, Thanksgiving in Canada was sometimes used as a tool for nation-building and the assimilation of Indigenous peoples into European culture. This complicates the holiday’s history and reminds us of the importance of acknowledging Indigenous perspectives and experiences alongside national traditions.

Modern Canadian Thanksgiving

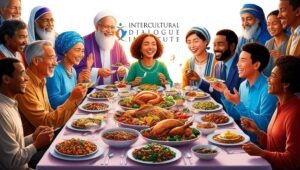

Despite these complex origins, Canadian Thanksgiving has evolved into a modern holiday focused on gratitude and togetherness. Since the 1950s, its meaning has shifted away from colonial myths and toward celebrating the good fortunes of everyday life: the roof over our heads, food on the table, and the company of loved ones.

Canadian traditions borrow from American customs—most notably the turkey dinner. While turkeys are native to North America, the idea of a large bird served at festive meals also has roots in England, where goose was more common. Alongside turkey, Canadians enjoy stuffing, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie. Football games and autumn hikes have also become part of the holiday for many families.

An Invented Holiday to Make Our Own

Christina Sismondo, writing in Macleans, suggests that Canadian Thanksgiving is essentially an “invented holiday”—a tradition pieced together over time. This gives Canadians freedom to shape it in meaningful ways. For children, Thanksgiving is often explained through themes of thankfulness and generosity. For adults, it becomes a chance to reflect on blessings, share with those less fortunate, and strengthen community bonds.

Whether rooted in faith traditions or simply in the practice of gratitude, Canadian Thanksgiving provides an opportunity to pause and appreciate life’s gifts. It is also an important moment to practice kindness and inclusion, ensuring the holiday is not just about feasting but about connection.

Gratitude and Community Today

At its heart, Canadian Thanksgiving is about gratitude—being thankful for what we have and sharing with others. As communities across Canada gather on the second Monday of October, the holiday is less about its complicated past and more about what we can create in the present: a culture of generosity, hospitality, and belonging.

From its earliest roots with Frobisher and Champlain to today’s family dinners, Canadian Thanksgiving has become a flexible tradition. It allows every individual and community to interpret and celebrate in their own way—making it not just a holiday of history, but one of shared humanity.